Carl Norden was enshrined in the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1994. The following is a summary of his career as presented in their citation.

Carl Norden was enshrined in the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1994. The following is a summary of his career as presented in their citation.

Carl Lucas Norden was born on April 23rd, 1880 in Semarang, Java,(now Indonesia) the third of five children. Following the death of his father in 1885, the family returned to Holland, then moved to Dresden, Germany in 1893. In 1896 he began a three year apprenticeship in a Swiss machine shop, after which he entered the world-famous Zürich Federal Polytechnic School. He graduated as a mechanical engineer in 1904 and came to America.

Norden worked for two years for the Worthington Pump and Machine Company in Brooklyn and from 1906 to 1911 at the J. H. Lidgerwood Manufacturing Company before moving to the Sperry Gyroscope Company. Elmer Sperry hired Norden to help design the first gyro stabilizer for large ships produced in the United States. While at Sperry, Norden married, and brought to America, Else Fehring who he had met years earlier in Zürich. In 1915, Norden left the Sperry company to set up his own business, but continued to work on Sperry's marine stabilizer contracts until 1917.

Norden worked for two years for the Worthington Pump and Machine Company in Brooklyn and from 1906 to 1911 at the J. H. Lidgerwood Manufacturing Company before moving to the Sperry Gyroscope Company. Elmer Sperry hired Norden to help design the first gyro stabilizer for large ships produced in the United States. While at Sperry, Norden married, and brought to America, Else Fehring who he had met years earlier in Zürich. In 1915, Norden left the Sperry company to set up his own business, but continued to work on Sperry's marine stabilizer contracts until 1917.

Norden won several patents on control systems for launching aerial torpedoes from ships. He also designed and furnished many instruments and devices for U.S. Navy bureaus, including robot flying bombs, radio-controlled target planes, and the catapults and arresting gear used on aircraft carriers. He also worked on a control system for aircraft, with others, which was a precursor of the automatic pilot.

In 1921, Norden began work on an instrument which could drop bombs from an aircraft and hit targets on land or sea. In 1923, Norden and Theodore H. Barth teamed up as partners and, over the next four years, Norden worked on the bombsight in Zürich while Barth assembled the parts in the US. In 1928, they incorporated their company as Carl L. Norden, Incorporated with an order for two precision bombsights. Barth became the president and Norden took on the engineering work. In the first year the company developed a new Bombsight with a timing mechanism to indicate the time to release the bomb.

In 1931, Norden demonstrated to the Navy a much improved bombsight in a test against the hulk of the heavy cruiser, Pittsburgh. Navy officials were so impressed by its accuracy they promptly ordered forty sights. The Army Air Corps also placed its own order.

The Air Corps, in 1935, installed Norden bombsights in Martin B-10s of the 7th and 19th Bomb Groups to develop the tactics of high-altitude, precision, daylight bombing. The first day of testing saw the B-10s coming within 520 feet of the targets from altitudes of 12,000 to 15,000 feet. By the end of the tests, the bombs were hitting within 164 feet of the targets.

To get bombs on target with acceptable accuracy requires an aircraft to correct for drift while maintaining a constant altitude and airspeed. Even minor fluctuations can cause a miss, and the greater the altitude, the greater the error. To overcome this problem, Norden devised a gyro stabilized automatic pilot. On the approach to the target, the autopilot would be turned on to reduce turbulence and "over controlling" by the pilot. The bombardier would take over and keep the cross hairs of the sight centered on the target. At the critical moment, the bombs were released and a green light in the cockpit would flash in the cockpit to tell the pilot that the bombs were gone and he could resume control of the aircraft.

In the succeeding years, the bombsight was improved. The ultimate model, designated the Mark XV, was a complex assemblage of more than 2,000 cams, gears, mirrors, lenses, and other components. With it, a fixed speed and altitude had to be maintained for only 15 to 20 seconds. Technically, the sight could place a bomb inside a 100-foot circle from four miles up. But, the bombardiers said it could "put a bomb in a pickle barrel from 20,000 feet."

At the beginning of 1941, the Carl L. Norden factory had planned an output of 800 bombsights a month, but the attack on Pearl Harbor caused immediate expansion of the facilities and production. By the end of 1943, nearly 2,000 Norden sights were being turned out monthly. So valuable were the secrets of the sight's manufacture that the plants were some of the most carefully guarded installations of the war. Norden himself was always accompanied everywhere by two bodyguards. Bombardiers were required to swear an oath to destroy any bombsight which had the potential to fall into enemy hands and bombsights were always covered on the ground and not unwrapped until the plane was airborne.

Production was halted on the bombsight in September 1945 after 43,292 units had been produced. The Army Air Force had procured all except 6,500 of the sights which went to the Navy. The Norden bombsight was used during the Korean War and on Strategic Air Command's photo reconnaissance and mapping missions in the early cold war.

Norden was a quiet and unassuming man who was proud that the bombsight could be used for strategically striking military targets while minimizing collateral damage to surrounding civilian populations and structures such as churches, schools, and homes. It's interesting to note that he didn't make money on the bombsight during the war, selling his rights to the sight to the government for one dollar. Carl Norden returned to Switzerland shortly after World War II and died there in 1965.

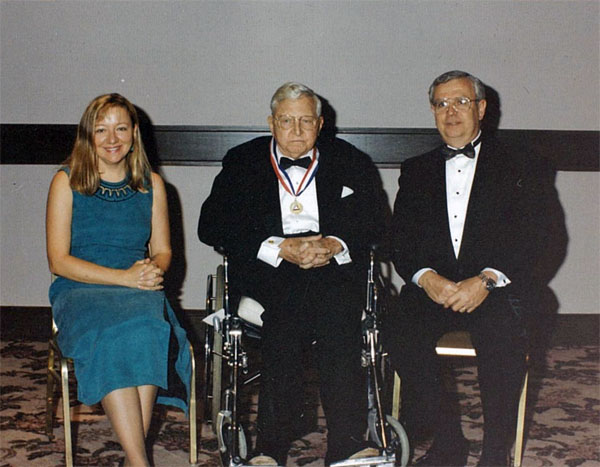

Below is Carl F. Norden, Carl L. Norden's son, in Dayton after receiving the National Aviation Hall of Fame award in 1994. Seated to his right is Elaina Norden, Carl L.'s granddaughter. Pictured also is Jack Wohler president of Norden in 1994.

Copyright © 1997 by NAHF. All Rights Reserved.