In the summer of 1937, the Luftwaffe asked the Abwehr (Defense Ministry) to obtain the design of the much heralded and super-secret Norden Bombsight. Queries to the operatives in New York brought the response that no one in the ring had access to it. In September, however, a routine shipment of documents arrived in Hamburg which included unidentified drawings with a note that the source worked at the Norden plant at 80 Lafayette St. and was eager to meet with a special envoy in New York.

At about the same time, Nikolaus Ritter returned to his native Germany after ten years as an unsuccessful textile manufacturer, rejoined the Army and was made chief of Air Intelligence in the Abwehr. His mission was to cover the air force and aviation industry of the United States. Ritter made plans to go personally to New York and organize the work, including the request for the bombsight.

In October, Ritter sailed aboard the Bremen for New York, checked into the Taft Hotel and began to establish a new identity as a German businessman. On the first weekend he took a cab to Brooklyn to talk to the man who had forwarded the unidentified drawings and arranged to meet with the source, codenamed “Paul”, on the next Sunday. It turned out this source was Hermann Lang, a 35 year old machinist and draftsman who came to the U.S. in 1927, was about to become a naturalized citizen and was employed as an assembly inspector at the Norden plant.

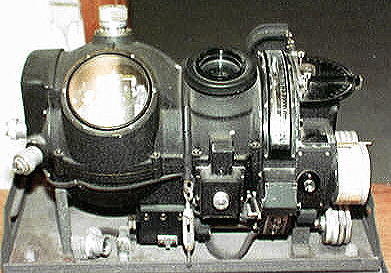

Lang explained that the bombsight manufacture was accomplished by different teams at different locations, even different companies, each having no knowledge of what the others were doing. One of his duties was to obtain and hand out drawings to the different teams and hold them overnight in a safe if they were needed again the next day. When he had overnight access, he would then take some home and, while his wife and daughter were sleeping, he would get out of bed, sneak off to the kitchen table and copy the drawings on tracing paper. He told Ritter he had a drawing of another assembly with him and could have more the next Sunday. He stated that he would not be able to get all the drawings, but he felt the talented engineers back home could fill in the blanks. His motivation appeared to be a desire to help the fatherland, having been presented with such an extraordinary opportunity.

Ritter was overjoyed at his quick success but faced the problem of getting what turned out to be an overly large drawing back to Germany. On the Bremen while coming to New York, he had met a steward who was in fact a courier for the Abwehr. He arranged to meet the courier at a drugstore and arrived carrying the drawing in a cane-umbrella. Having left ship and gone through Customs without an umbrella, the courier refused the delivery but arranged to come back the next day with his own umbrella. The next day was very sunny, so the man had to effect a limp and justify the umbrella as a cane. The next Sunday Ritter received more drawings and gratefully paid Lang $1500, the largest lump sum as yet paid by the Abwehr to an American agent.

The Germans proceeded to build a model from the drawings, but because of the missing pieces, it would not work. Ritter contacted Lang in New York and with the aid of a 10,000 mark expense account, induced him to come over and help. When he arrived they showed him a now finished model of an "improved" bombsight, so he spent the week being feted by the Abwehr and was even received by Hermann Goering.

In 1945, Patton's Third Army came upon a hidden factory in the Tyrolean Alps and captured its secret product. On examination by the U.S. technical intelligence team, it turned out to be a copy of the Norden bombsight.

----------------------------------------------------Sources: Hitler's Spies, David Kahn, Macmillan

The Game of the Foxes, Ladislas Farago, McKay